Note that this only applied after you’d been charged in court. It did not apply to usual police interrogations that take place before you’ve been charged.

If you want to see just how frustrating the unguided “voluntariness” approach was, just try to read Frankfurter’s opinion in Culombe v. Connecticut, in which he tries for pages and pages and pages to make sense of it and justify it, but in the end only proves what a mockery it had become. It’s kinda sad, because he’d believed in it for so long. A simple guiding principle along the lines of common-law entrapment doctrine would have sufficed (i.e., if the subject had originally not intended to confess, and the police threatened or cajoled or otherwise made him change his mind, then the confession was per se involuntary). But…

How crucial are interrogations to modern law-enforcement? Are most criminal cases impossible to resolve if no one ever confesses to the crime or do the confessions extracted from interrogations just save time?

They’re still very crucial in many cases. Not when the police witnessed the offense, or when there’s plenty of eyewitness or forensic evidence, but still often enough.

It’s sad to say, but it’s true that in lots of cases a confession may be just a time-saver. Those aside, however, the most serious offenses are often unsolvable without one. CSI isn’t quite as amazing as it seems on TV, and reliable witnesses can be hard to come by (especially when the only witness is dead).

As for being a time-saver, what’s wrong with that? If you’re pretty sure you’ve got the culprit, why spend time and tax dollars building a circumstantial case when you can get his own words for evidence? Very few detectives try to extract confessions from people they don’t think did it, after all. They really are trying to do the right thing.

The problems come when they place too much faith in their own conclusions — especially when that faith has been falsely enhanced by training based on unsound, unscientific psychobabble. A good detective is full of healthy skepticism, not template conclusions. But I digress…

Its not that saving time is a bad thing. After all, a law-enforcement agent’s time translates into taxpayer money whenever they are on the clock. However, if the only method of saving time has a significant risk of extracting a false confession and getting the wrong person punished, then one would hope that law enforcement entities would do a risk/reward analysis before attempting to save time via an interrogation. That being said, I do understand why the police use interrogations in cases that are unsolvable without a confession, because then they don’t have a choice.

Thats a bit of a misreading of what he just said. Detectives aren’t using confessions in unsolvable cases: They are getting confessions when they already know who did it and, since they already know who did it, then benefit minus cost is positive.

The problem isn’t that they don’t know.

The problem is that they know something that just ain’t so.

Sorry, I should have been more clear. By “unsolvable case” I did not mean a case where discerning who did the crime is impossible. I meant a case where convicting the person who did the crime is impossible unless they confess.

A little off topic, but apropos: with the recent ruling by the Court that the police can haul you away so another person in the house can give consent, I started thinking of the “feather,” tangently and came up with: I have a friend who is very good friends with a law enforcement officer and they both come to my home occasionaly. If the officer, as an invited “off duty” guest, were to notice the “feather” in my collection, could he arrest me and seize the “feather” for evidence?

Hmm, well, 1964. Important decision that year. Another one a couple of years later. Not hard to guess what you’ll be covering next.

Is that a Three Degrees/third degree pun I see there?

Hey Nathan,

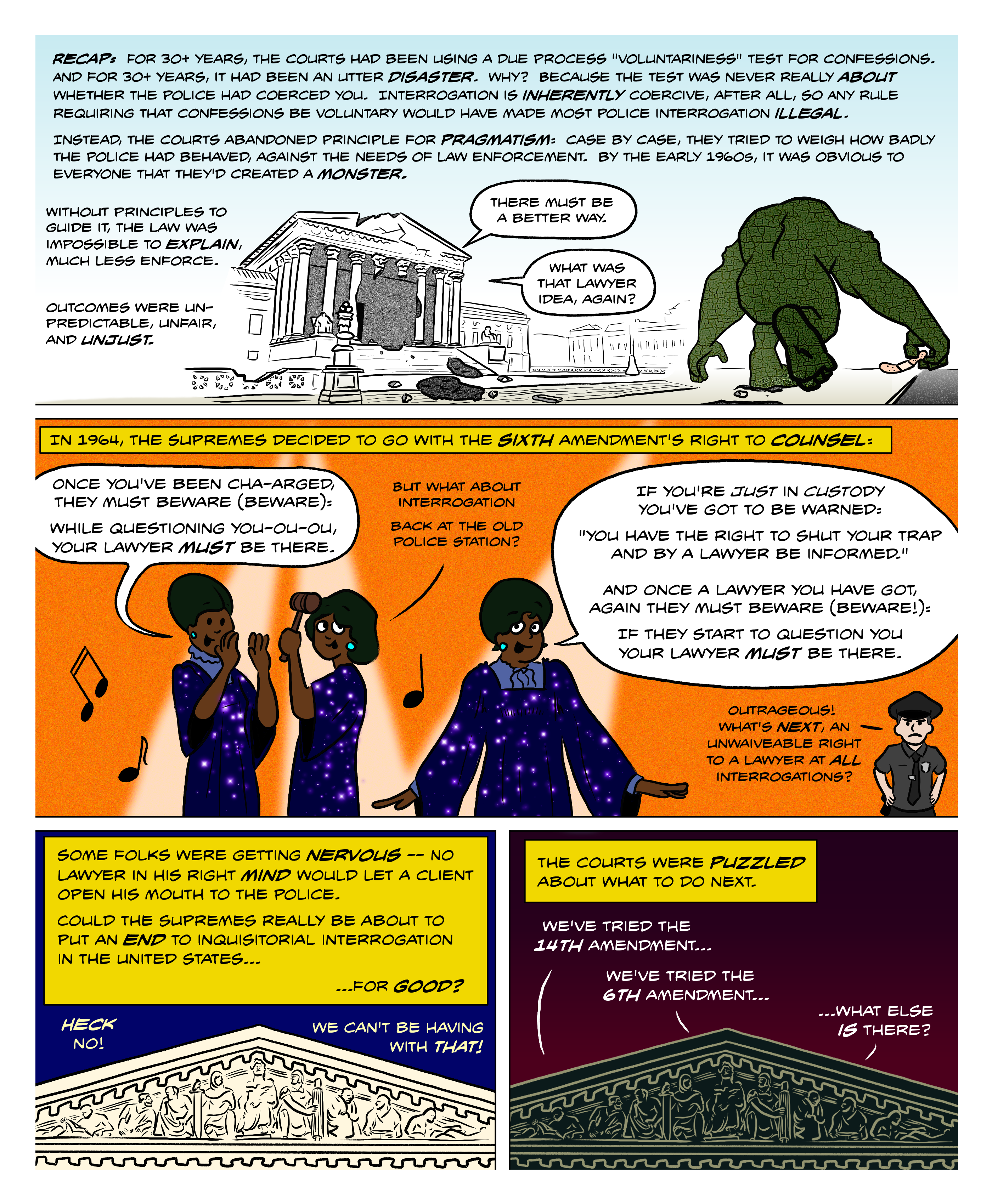

Is the 1964 case you’re referring to Escobedo or Massiah?

I’m having a hard time understanding there real-world impact of Massiah. Is it actually relevant, or do the police just manage to get all their interrogating done before formal charges are filed? (In other words, does it suffer the same problem as the right to counsel for lineups, for the reasons you discuss in this strip? https://lawcomic.net/guide/?p=3623).

LaFave says the Massiah rule is “conducive to manipulation by the police” — is that code for “completely irrelevant”? And if so, how did the police screw up so badly in Brewer v. Williams?

P.S. Learning about the “Christian burial speech” was what first got me hooked on criminal procedure years ago.

I like the meme.

Thanks!