|

This is a purely educational website. Nothing here is legal advice or creates or implies an attorney-client relationship. If you have a specific legal issue, PLEASE talk to a lawyer who practices where you live—laws vary from place to place, and how they're applied varies from courthouse to courthouse. Your local county bar association can probably refer someone who handles matters like yours.

By using this site, you agree that you are awesome. Use of this site also constitutes acceptance of its Terms of Service and Privacy Policies, which are known to medical science as a cure for insomnia.

It's best to keep all discussions in the comments. But if you really need to reach Nathan privately, go ahead and email him at n.e.burney@gmail.com. He won't mind.

THE ILLUSTRATED GUIDE TO LAW and the PEEKING JUSTICE logo are pretty damn cool trademarks and should probably be registered one of these days.

© Nathaniel Burney. All rights reserved, though they really open up once you get to know them.

|

|

So… if someone who hadn’t been read his rights was on pain meds, concussed from a gunshot, and pleading to be left alone in his hospital bed or to see a lawyer, would his statements be admissible?

https://c.o0bg.com/rw/Boston/2011-2020/2014/05/07/BostonGlobe.com/Metro/Graphics/tsarnaev_motion.pdf

Patience…

Er, oops. I’m doing that thing again where I try to get you to jump ahead of what you’ve already covered.

Also, I shouldn’t be one-sided, so here is the prosecution response to the motion to suppress:

https://www.scribd.com/doc/225641540/Justice-Department-Motion-Dzhokhar-Tsarnaev

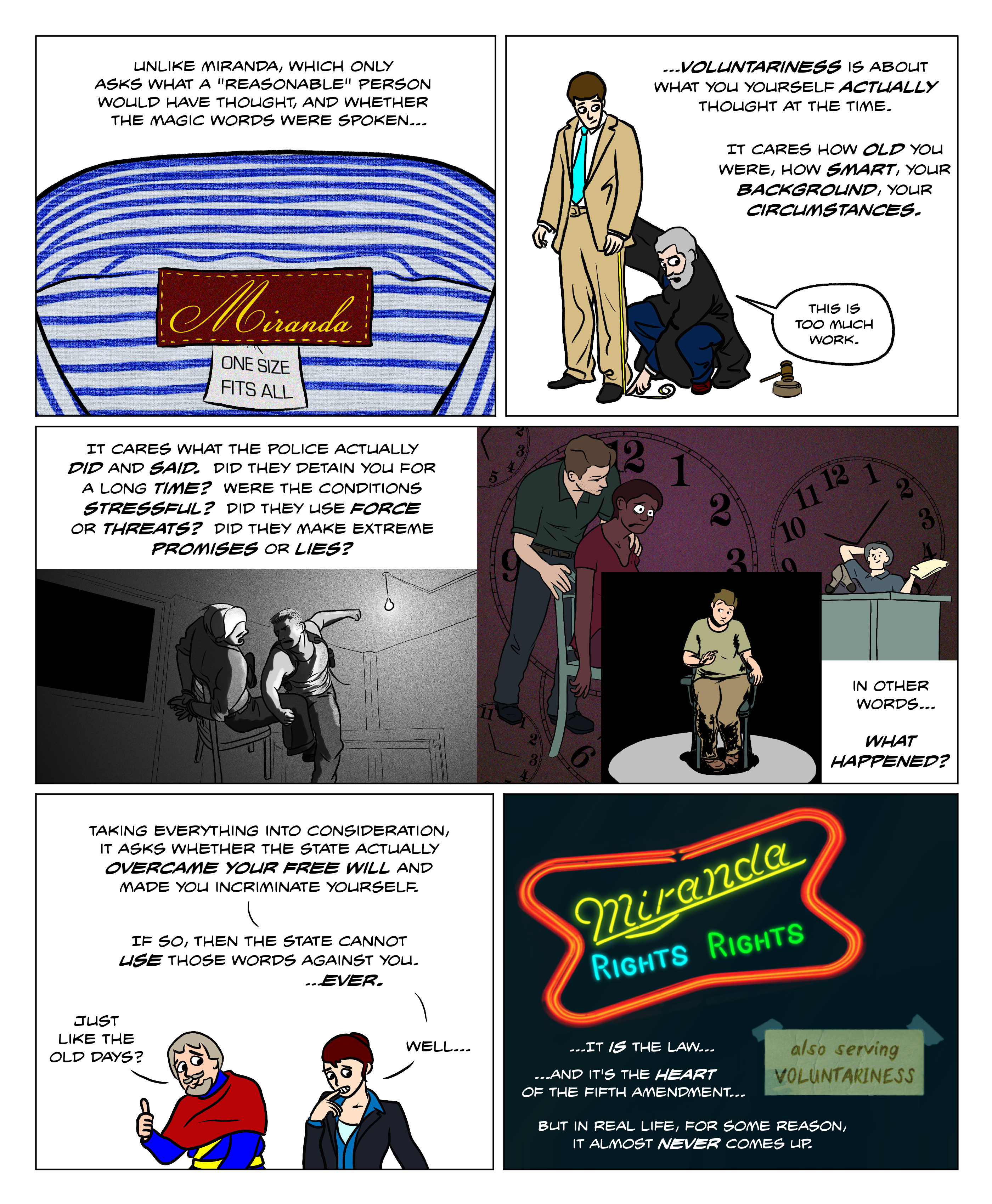

With respect to voluntariness, the two motions are worth reading. Though actually, for a non-lawyer, they’re probably not all that easy to follow. Especially the defense one. Let me see if I can sum up:

Tsarnaev’s lawyers said the statements were involuntary because (1) he was in the hospital recovering from severe injuries, (2) his injuries and medication affected his ability to think, (3) he wanted a lawyer but wasn’t given one until the interrogation was over, and in fact was told he would not be given one until the interrogation was over, (4) the interrogation took place over a two-day period, (5) at various times, he asked them to pause questioning until later because he was exhausted or not feeling well, and (6) although the government could have charged him sooner (which would have gotten him a lawyer and effectively ended any interrogation), they chose not to do so until they’d finished with their interrogation.

On the face of it, the defense argument is kinda weak. It does marshal a few relevant factors to consider — length of interrogation, mental ability, stated desire to stop talking — but it never makes a good case for how the agents took advantage of these circumstances to draw out statements Tsarnaev didn’t want to utter. The argument isn’t clearly made, and spends a lot of time on irrelevant tangents.

The government said the statements were voluntary because (1) the mere fact that Tsarnaev was tired and medicated doesn’t make the agents’ questioning coercive, (2) the questioning took place in a lot of short chunks spread out over two days, with breaks in between, not all at once, and it took that long only because of his own difficulty in speaking, (3) they waited more than 24 hours until he was stable and lucid before they started, (4) they never threatened or intimidated him, (5) they never made him uncomfortable, and in fact helped make sure he was comfy (6) they didn’t make promises or inducements, (6) they didn’t engage in improper deception, though they didn’t tell him his brother was dead, (7) the agents weren’t in uniform, their weapons weren’t visible, and they behaved gently, (8) when he seemed tired, they stopped and recommended that he rest, (9) not reading someone their Miranda rights isn’t coercive, (10) not getting someone a lawyer isn’t coercive, (11) his painkillers made him more lucid, not less, and (12) Tsarnaev was clearly willing to answer questions, and never said he didn’t want to talk any more, only requesting pauses at most.

On the face of it, the government makes a very strong argument. It goes through all the relevant circumstances and explains how none of them would indicate that the agents overcame Tsarnaev’s free will. I would be very surprised if a judge disagreed.

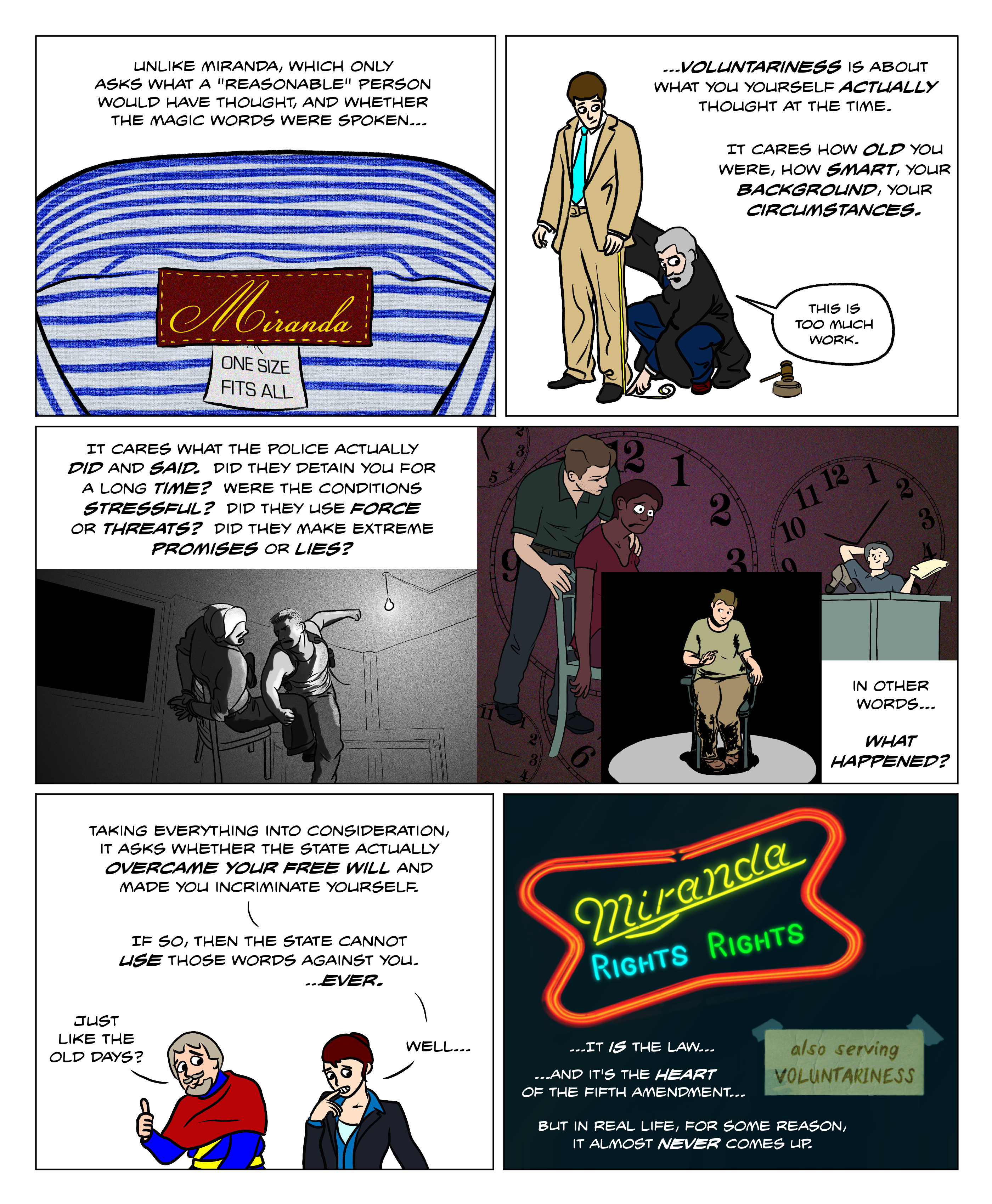

Although we are going to get into this in more detail later, I ought to point out that voluntariness is the only important issue here. The feds aren’t going to use Tsarnaev’s statements in their direct case at trial. They only want to be able to use them if Tsarnaev testifies differently at trial, to show the jury that he said something else when questioned. That’s called “impeaching” his testimony. If the government merely violated Miranda, they’d still be allowed to use the statements for impeachment. But if they forced him to make the statements involuntarily, then they can never use them, not even for impeachment.

Which makes it kind of a shame that the defense didn’t do a better job arguing voluntariness. But hey, at least they did!

” the agents weren’t in uniform, their weapons weren’t visible, and they behaved gently”

Hmmmm so the government admits that uniformed agents with visible weapons are inherently coercive…

Not quite. It can certainly be a factor that contributes to a finding of coercion, but it’s not inherently coercive.

Saying the factor didn’t even exist is not the same as admitting it’s something it isn’t.

I’m not sure I follow that logic. The government would only bring up the uniform/weapons if it impacted voluntariness in some manner, right? Since we have a magnitude, we now need a direction of this voluntariness. Are people going to feel more like they can refuse to speak in the presence of someone with a uniform and gun, or are they going to be intimidated into saying something whether or not its true?

How can something contribute to a situation being coercive and not in itself be inherently coercive?

Being a contributing factor isn’t the same as being the entire reason. If I quit a job, I might cite low pay, lack of respect from management, long hours, low vacation time, and poor benefits as my reasons. But I might also say that while all of those contributed, none of those were solely responsible for it. If I’d had low pay but other things were fine, I might stay. If all of those factors were there except there was a ton of vacation time available, I might stay.

In that same way, uniformed and armed police might be inherently *more coercive* without necessarily being coercive themselves.

Yeah! Phronesis FTW!

Does the defense council have to worry about conceding facts in this motion? it feels like they are stating as fact things that could be used to incriminate their client: Like, that he was involved in a gunfight.

That does bring up another interesting question. Can statements made by the defense at suppression hearings ever be used against them at trial?

I really don’t see why not. Harken back to ye olde days of confessions when the folks were up in front of the congressional panel.

This won’t be covered until we get to Advanced Crim Pro, as it’s something that concerns lawyers rather than individuals or cops. The short answer is “yes.” The more detailed answer is gonna have to wait.

Does this (statements made in suppression hearings useable in trial) mean it’s possible to plead the 5th in a suppression hearing and discredit their evidence during the actual trial instead?

Testifying at a hearing waives your Fifth Amendment privilege automatically. You can’t take the stand and give testimony and then take the Fifth if they ask questions you don’t want to answer.

What is far more common is for defendants not to testify at all during a suppression hearing. Just let the government put their cop on the stand, and let the defense attorney cross-examine him. (And the government can’t call the defendant as a witness, of course.)

The issue is more likely to arise in the written motion itself. (Typically, the defense lawyer writes a motion seeking suppression, the prosecutor writes a response, and then the judge decides to have a hearing.) Isn’t there a risk that assertions made in the motion papers could be used against the defendant? The motion issue varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and even courthouse to courthouse. Some require the defendant himself to swear out an affidavit that provides sufficient facts to give him standing and to support his motion. This can be damning, and requires a lot of care and thought on the part of the lawyer, who might decide it’s not worth the exposure. Other jurisdictions let the lawyer make a bare-bones assertion without making the defendant say anything, which makes the written motion far less of a concern.

Very informative as always, thank you.

Thank you for the informative explanation. Just to clarify, this applies to suppression motions/hearing tesimony only, right? Or are there other types of motions that would force a waiver of rights if performed?

I would think that reasoning would apply to *all* written motions, though it would come up most often in motions to suppress.

How about the Writ of Habeus Corpus?

Actually, ever since that guy’s bit, I’d been wondering – what about the UK? Don’t the police there now not only have to warn against self-incrimination as well, but also that your silence can be used against you? Is the presumption of voluntariness as strong there as it is here?

English law evolved there on different lines in the 20th century. They had warnings well before us, but as you say they may also use it against you if you choose to remain silent. According to this fairly current summary written for English police officers, the “caution” is as follows:

You do not have to say anything. But it may harm your defence if you do not mention when questioned something which you later rely on in court. Anything you do say may be given in evidence.

FWIW

I know you aren’t an expert on English law, but would “I am an American citizen. I do not understand the full significance of the caution you just gave me. I wish to speak to the American Consul before being questioned.” be a reasonable reply to the caution?

If the answer to this is not “yes”, then we have a problem.

Poor Old English Lord. You can see in his face he’s thinking “things used to be so much simpler. Maybe things are fairer in this strange future time, but they’re also so complicated it takes an expert to even understand what’s going on.”

You do have to wonder sometimes how much of it is necessary for justice, and how much is just “the way we do things”. Could it be made simpler for the ordinary person to understand without sacrificing too much?

Of course it could be simpler. You could just say it’s not usable if legal counsel isn’t present unless person specifically states that they will act as their own counsel (no simple “yes” or “no”).