|

This is a purely educational website. Nothing here is legal advice or creates or implies an attorney-client relationship. If you have a specific legal issue, PLEASE talk to a lawyer who practices where you live—laws vary from place to place, and how they're applied varies from courthouse to courthouse. Your local county bar association can probably refer someone who handles matters like yours.

By using this site, you agree that you are awesome. Use of this site also constitutes acceptance of its Terms of Service and Privacy Policies, which are known to medical science as a cure for insomnia.

It's best to keep all discussions in the comments. But if you really need to reach Nathan privately, go ahead and email him at n.e.burney@gmail.com. He won't mind.

THE ILLUSTRATED GUIDE TO LAW and the PEEKING JUSTICE logo are pretty damn cool trademarks and should probably be registered one of these days.

© Nathaniel Burney. All rights reserved, though they really open up once you get to know them.

|

|

I was waiting for this slide. Kinda like watching the movie Titanic the first time…you know what’s coming, but that doesn’t take away from enjoying the story that leads up to it.

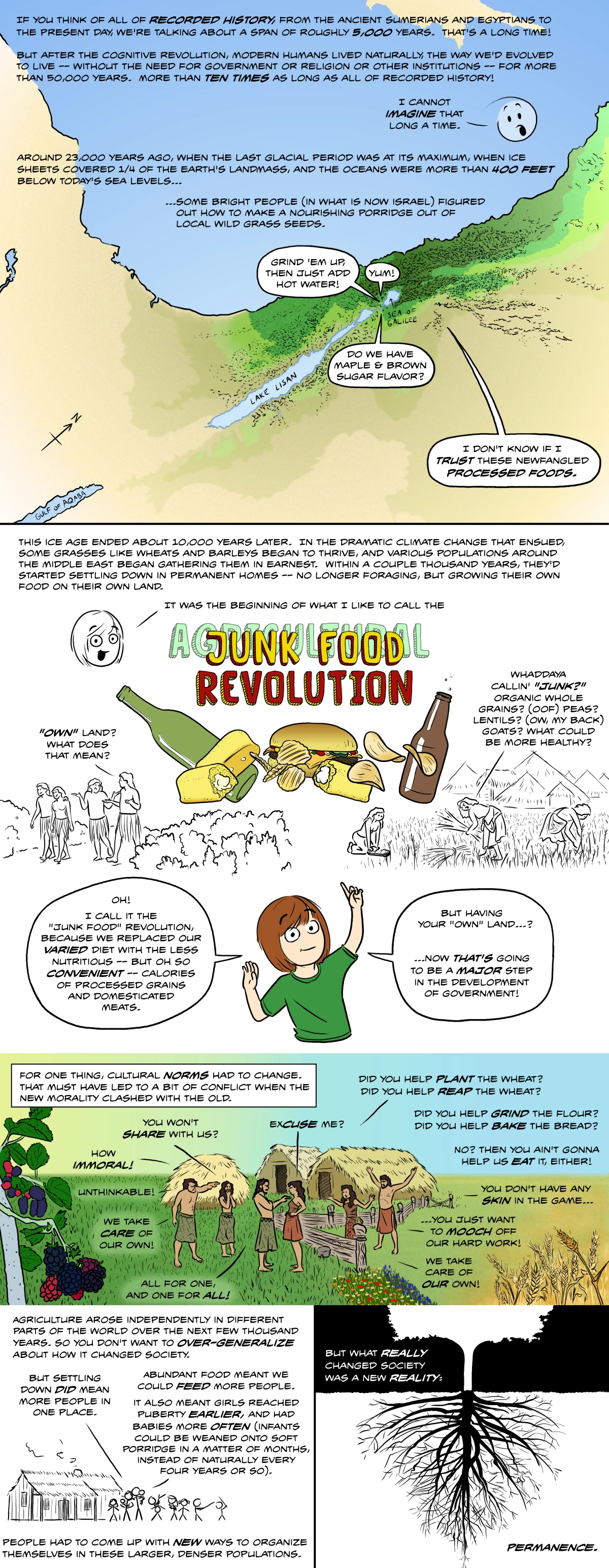

I really, really love your “Permanence” panel. Using the black & white negative to echo the abrupt change taking place, plus exaggerating the root structure to symbolize the magnitude of this change, and the choice of a tree and its roots to reinforce the meaning of “permanence”, was all very artistic and visually effective.

Thanks, Stephen! I’ve been looking forward to this one, too (though it’s nothing at all like I originally sketched it out many moons ago). And I’m very glad you appreciated that last panel!

There is a theory in political economy that preferences for redistribution of income is directly proportional to variability in income over time. When income is highly variable over time, even the wealthy will favor that wealth be evenly spread to a certain extent, because they will know that they can easily be poor tomorrow. By that same logic, when income is fixed over time, the wealthy have no incentive to favor income redistribution, because it will only ever be a loss for them. The poor always favor income redistribution, because it can’t be a loss for them. In a society with highly variable income over time, the poor could be the rich tomorrow. But they can easily be poor the day after tomorrow. So they still benefit from redistribution. When income is predictable, redistribution is only ever a gain for the poor. So they support redistribution regardless.

I wonder if that is what happened with the Junk Food Revolution, just with food supply instead of with money income. So by that logic its not so much land-ownership that led to the decline of sharing as it is the rise of reliable food supplies. When food supply is unpredictable, enforcing sharing makes sense, because you will need others to share with you later even if you don’t now. But when food supply is predictable, enforcing sharing only makes sense for the people who have no food, and starving people have very little political leverage, since they don’t make good politicians or revolutionaries.

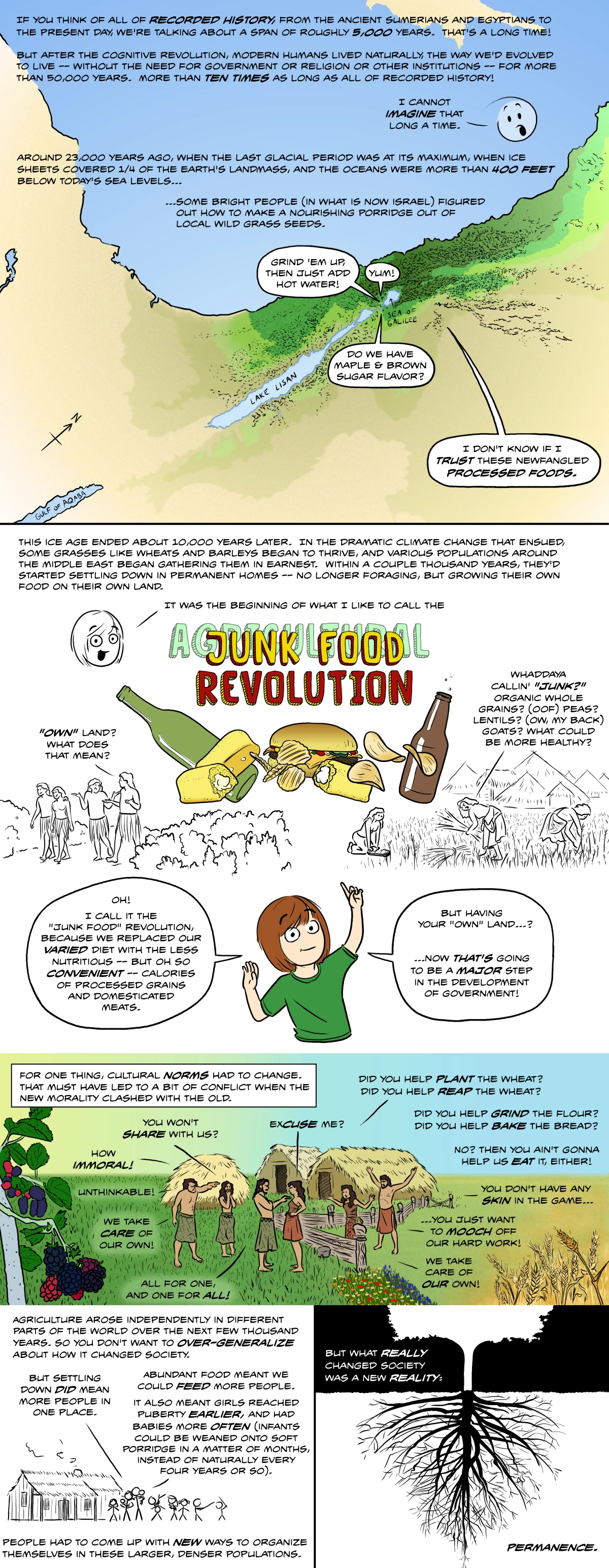

You make an excellent point. And I made mine inexpertly: it wasn’t that owning land changed the willingness to share, it was the new reality of what counted as having skin in the game, of being invested enough in the team to be worthy of sharing in its produce.

To a band-level forager, the mere fact of being a member of the team meant you got an equal share in the food, regardless of whether you had a hand in finding THIS particular meal. Refusing a share of the food was theft! Stealing from a fellow bandmate.

But to a farmer, demanding a share without sharing in the labor to help grow and process the food? THAT was stealing. It was a huge shift in world view, a drastic change in our very perception of reality. (And there were more to come! All the way up to modern-day political differences.)

That kind of fits with the redistribution theory you mention, but then again the entire band would be farming. And probably all of its neighboring bands. So as a farming band, the norm would be everyone pitches in. The story of the Little Red Hen would have been about an asshole bird to a forager, but to farmers it’s a story of fairness and basic common sense. As everyone lives by the norms as a rule, there wouldn’t be very many people who DIDN’T pitch in. If you were starving, so was everyone else.

Each society was very much homogeneous and very much on the same page about right and wrong and how life is lived. It wouldn’t be until the rise of heterogeneous societies encompassing multiple cultural worldviews that you begin to see the need for political leverage or revolutionaries.

“So as a farming band, the norm would be everyone pitches in.” Isn’t that also the norm for foragers? You said earlier that in forager bands, if you can’t even keep up with the kids and the elderly, you get left behind or killed. If the point of that wasn’t to make sure that everyone pitches in, then what was it?

Yup. Cooperation was the name of the game for foragers, and it was still the name of the game for farmers. But what counted as cooperation had changed. I’ll be touching on this in a little more detail.

But the point of excluding the unhelpful wasn’t to coerce people into being helpful. It wasn’t a way to compel future behavior, but to react to present conditions. Properly socialized, you wouldn’t have a fear of exclusion driving your behavior; you’d act right because it was the right way to act, it felt right.

Perhaps there was coercion of a sort in normal socialization, where individual urges had to be suppressed by one’s conscience and the gentle nudging of one’s peers, but it’s not the kind of power struggle I think you’re envisioning. Everyone in a particular band, whether foraging or farming, was in agreement over what was right and what was wrong. And each one had the same voice as the others. It’s not until you get cultures mixing, people with different senses of right and wrong living together, that you start seeing compulsion of norms by more powerful segments of society. We’re not quite there yet in the comic, but we’re getting there!

If power-struggles were not what drove the change in norms around food sharing, then what did? In other words, why do foragers consider it right to share with everyone whether they had a hand in this particular meal or not? and farmers only consider it right to share with those who did contribute to this particular meal?

Conflict between foragers and farmers would have been rare, because where farming happened, pretty much everyone settled down to farm. The agricultural revolution didn’t happen overnight, but gradually over a period longer than the entire time monotheism has been a thing. And the cultural shift was just as gradual. And all of this didn’t happen in isolation—it couldn’t have happened within one band but not its neighbors.

So what drove the change in norms what not conflict, but rather the gradual change in daily reality.

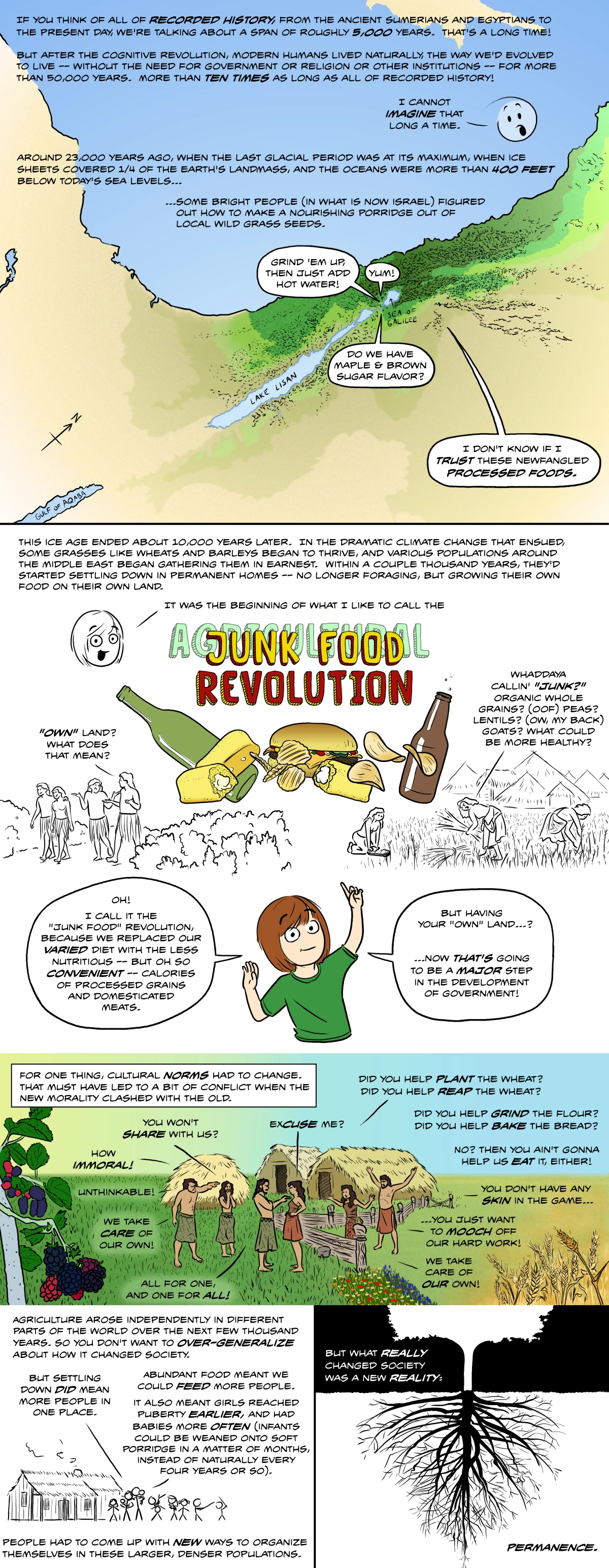

Imagine you’re a farmer in what is now Lebanon, sometime around 8,000 B.C. Three thousand years before you, your forager ancestors were living lives fundamentally different from yours. But they had been gathering wheat for a long time already, taking it back to wherever they’d camped nearby to grind it into something edible. As they followed the seasonal patterns, they were starting to notice that more wheat was now growing along their paths between the wheat patches and their camping grounds. Some was even growing at the campsite. Over time, they realized that the new plants grew where seeds had been dropped before. They started planting it on purpose, ensuring a bigger supply next time. The wheat-gathering season eventually stretched out to weeks, then months, until maybe a thousand years ago they—like practically every other human band within a couple hundred miles of them—had settled into permanent villages. For a thousand years, now, your people and all their neighbors have been cultivating wheat and other grains, eventually raising pigs, herding goats. All along the way, each change was tiny, practically unnoticeable. Similarly, your ancestors’ concepts of right and wrong, and their day-to-day reality of how life is lived, evolved just as slowly and invisibly. Each of them must have felt that people had been living precisely the same way as you since forever. But you’ve never even heard of foragers, and their ways of life and their realities and their norms would have seemed alien to you.

So the norms changed because normal life changed. They’re not what’s imposed, but what’s normal.

It will be several thousand years yet, and another major societal revolution, before anyone starts imposing norms on anyone, or engaging in power struggles of the sort you’re envisioning. It’s hard to imagine this, because the world of paleolithic bands and the world of neolithic farmers are entirely alien to the world we’ve known since the dawn of recorded history. But that’s how it was.

Ok, no one imposed anything on anyone. But what is the connection between foraging/sharing with everyone and farming/only sharing with those who actively contribute? Is it a purely economic phenomenon where foraging really doesn’t require that much labor, and the labor it does require is sporadic, so people who don’t contribute to this particular meal can still be counted on to contribute later? Whereas with Farming, labor becomes so valuable and so consistently required that refusing to contribute stops being an inconvenience and starts being a threat to the entire system? Or is there something else going on?

> “The poor always favor income redistribution, because it can’t be a loss for them.”

Careful. The poor may always have an *incentive* for income redistribution, but people are complex. Today you’ll find lots of people with well-below-average income who are against proposals like universal basic income (and a fair number with well-above-average income who are in favor).

Wow. I don’t understand why I didn’t strike this insight earlier, but there’s something in this post that just triggered it now.

I married a Filipino. In her language is a word that I took a long time to learn. It’s “kuripot”, pronounced ku-RAY-put. When I went to the Philippines to marry her, I was called this, and at first I thought it meant stingy or miserly. There were many times where I was asked to help pay for meals, gifts, drinks, or entertainment. Since this wasn’t in my budget, I had said no, and I thought my new family was just saying I was cheap.

But years later, I learned it has a much deeper meaning. The best way I can define the word is, “When one doesn’t share the benefit of ones fortune with family and friends.” In most of the neighborhoods, families are pretty poor, and it’s socially expected to share in good fortune with others when it comes one’s way. When the money is gone, it’s gone, so enjoy it while you have it. Go to the bar and buy everyone a round. Have a nice meal at your house and invite your friends. Rent a videoke machine, buy a few bottles of rum, and have a party. Or, if a family member is in the hospital, help pay for their bill. If someone’s in jail, help with their bail. See a cousin with an old pair of shoes, buy them a new pair. That sort of thing. In a significant way, it’s a social insurance. Like the offering plate at church, it’s not -required-, but it’s -expected-. Because when it’s your turn to need assistance, you want others to be there for you too.

But my wife immigrated to the United States, has a job, and has disposable income now. It’s created many interesting (difficult, but interesting) complications. Because while her family expects her to provide a share of her fortune, and she does to an extent, she now feels the ownership of the capital she has worked so hard to earn. And when she sees her family consume her benefits without a respect or appreciation for what it took to earn it, it’s very frustrating for her.

More interestingly, we have this social expectation in the United States as well. I saw it first-hand while living and working in a poor rural county. People living around the poverty line have the same behaviors. Except we don’t have a word for it. But we kinda have an expression…”You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” It almost seems like this dichotomy is a part of our humanity. We seem quite selfless when our labors are performed for communal survival, but it becomes selfish when the purpose of that labor shifts to individual survival.

So if porridge is about 23000 years old, I wonder how old the concept of tea (as in, plant parts in boiling hot water to make a beverage) is … probably older?

Tea is much, much older. Far older, even, than Homo sapiens. There’s goodevidence that Homo erectus folks were steeping tea leaves (Camellia sinensis) in boiling water as long as five HUNDRED thousand years ago—in other words, just as soon as they figured out how to control fire!

This raises all kinds of cool linguistic questions and cultural inquiries, which I am now going to ignore while I go put the kettle on.